Sixty miles down below

Where we set off today in London we will be treading on two thousand years of human rubbish still piling up slowly over ashes of past fires and burying rivers like the Fleet and the Walbrook where the romans put their feet. As a school boy, I joined archaeologists scraping through medieval cess pits, amazed at the ladders I had to climb down to reach the roman remains below.

When we set foot by the muddy Thames today, we won’t be the first people on this particular patch of the Earth, but nor were the Romans, Angles and Saxons who gave our places names and wrote them down. The first people did not arrive by boat or write stuff down, but wandered up here, perhaps like us, seeking better times ahead, but before we get to those ancient barefoot dreamers later on this page, lets think of all the other creatures that died below our feet long before we started leaving our bones, rubbish and impressions behind.

Its not just our lives that have been piling up rubbish, every living thing in the marshes, lakes and seas has been throwing out its rubbish into the water we drink, the air we breath or the ground we tread.

If we could walk just sixty miles down we would be right through the thin cool skin of debris we are treading today. Just below the crust, our planet is still red hot liquid rock, rising and fallng under us as turbulent as the water in the sky aboeve and occasionally bursting through the crust, belching volcanos high into the atmosphere to fall back as ash with the rain or ooze out in scorching new rock as sterile but fertile rock to be ground down under the wind and weather and the miracle of life.

On our route today we don’t expect to see active volcanoes belching new rocks to the surface, but after we leave the constantly swept streets of London we may tread on litter dropped or buried by humans, some lasting weeks and some lasting centuries. Just beyond Cambridge, a few watery fens are still leaving their life’s debris behind, preserved by the airless waterlogged peat to create new fossil fuel from the sun, dirt and air. Much has been darained, burnt or blown away over the last two centuries.

A thin rocky skin

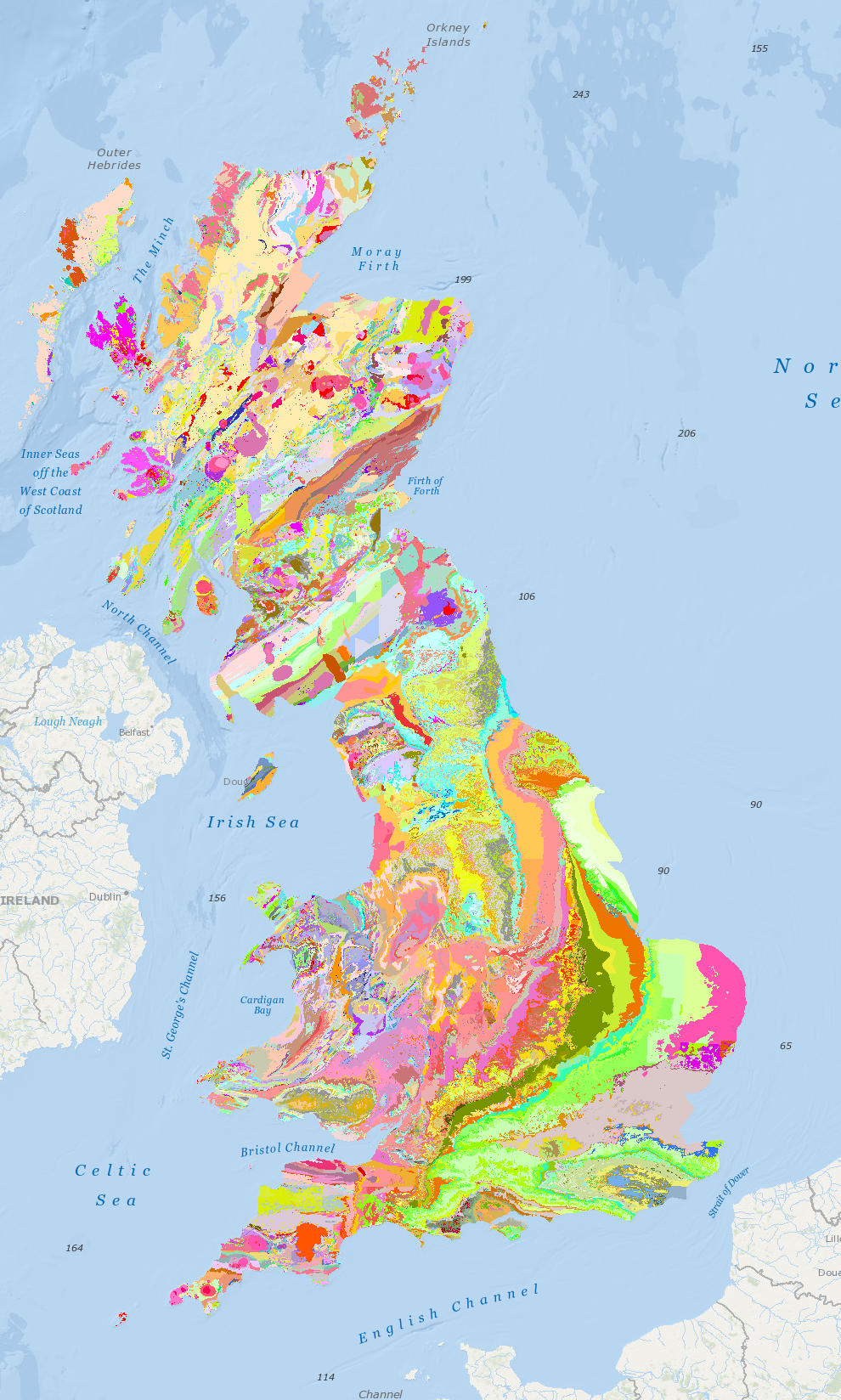

Planet earth formed 4,600 million years ago, a molten blob of chemicals spinning around the sun. In the Britain the oldest rocks breaking the surface today are at the top far north west of Scotland and were formed about 3000 million years old when earth was cooling down enough to form a crust for the first time and the earliest forms of single celled life were forming as water condensed and the weather cooled down. However, when they formed they were nowhere near here where we are walking today.

Scotlaand was not connected to England and both countries were way down in the southern hemisphere on separate super continents. Scotland was 20 degrees south of the equator and England was right down at the antartic circle.

As life moved on and the continents drifted around at about the speed our hair grows each wave of life left its own debris on the surface to form the rock layers that are crumpled split and bashed together in the picture below. By the time of the dinosaurs 200 million years ago England had made its way to 40 degrees north of the equator and the younger rocks we will be treading today were formed.

We won’t travel as far England has come today, but we will should surpass the speed of hair and overtake our drifting continent of europe still pushed north by Africa like the first people who crossed the rising alps on foot to get here.

View north from the still rising alps

The youngest bed rocks on the map above are in the south east under London and formed pretty much where they still are today, right up here in the temperate northern hemisphere where they have been here for the last few million years since well before people first stood tall and considered themselves to be a breed apart from their knuckle dragging parents as they trod their separate paths over the crumbling surface together. At the time around 50 million years ago Africa had squashed a vast ocean into the tiny mediterrean sea that is left today making the alps the high mountains they are today and putting enough pressure on faraway England to buckle the newly formed chalk into the ups and downs that started filling with London’s clay.

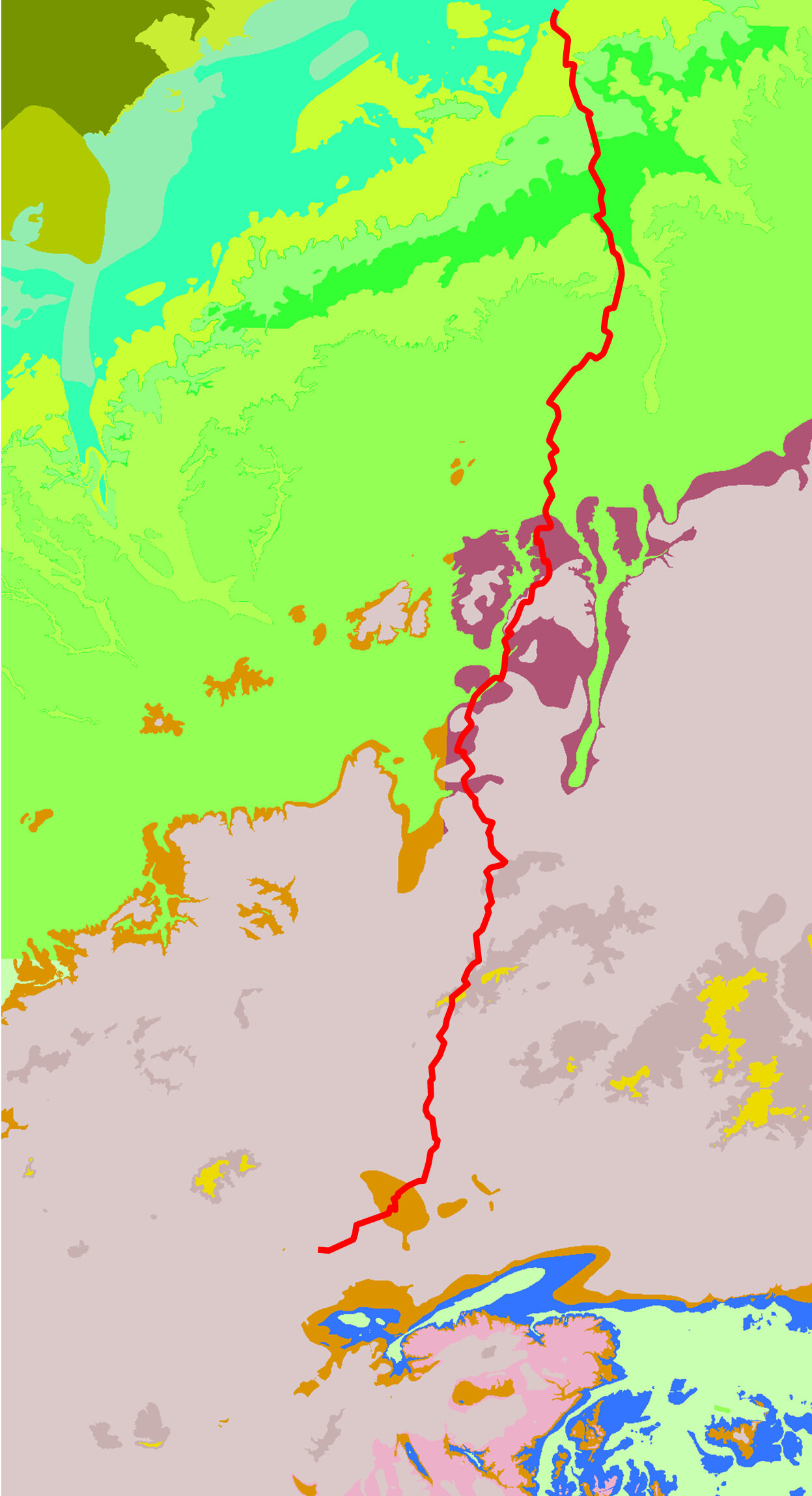

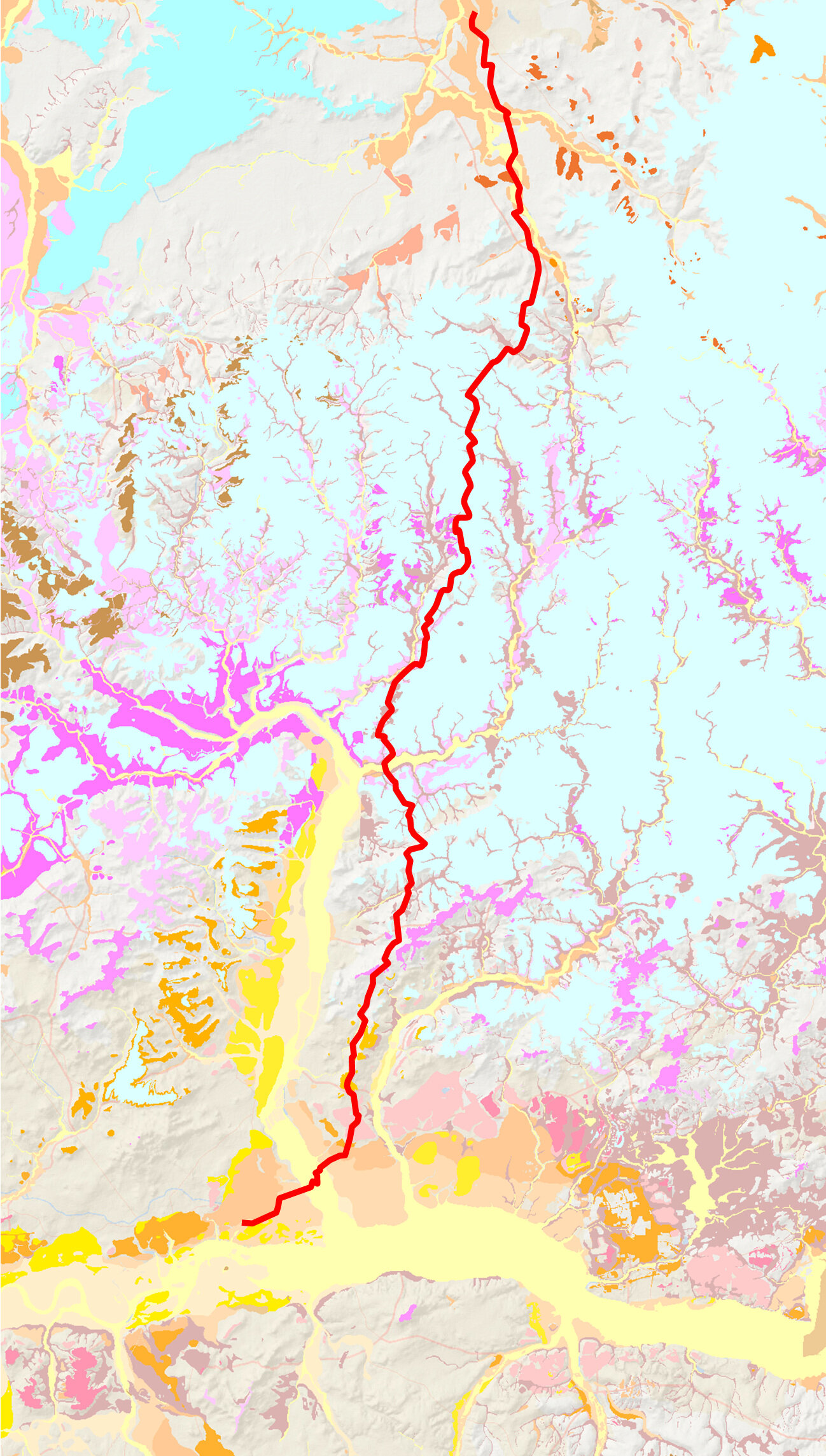

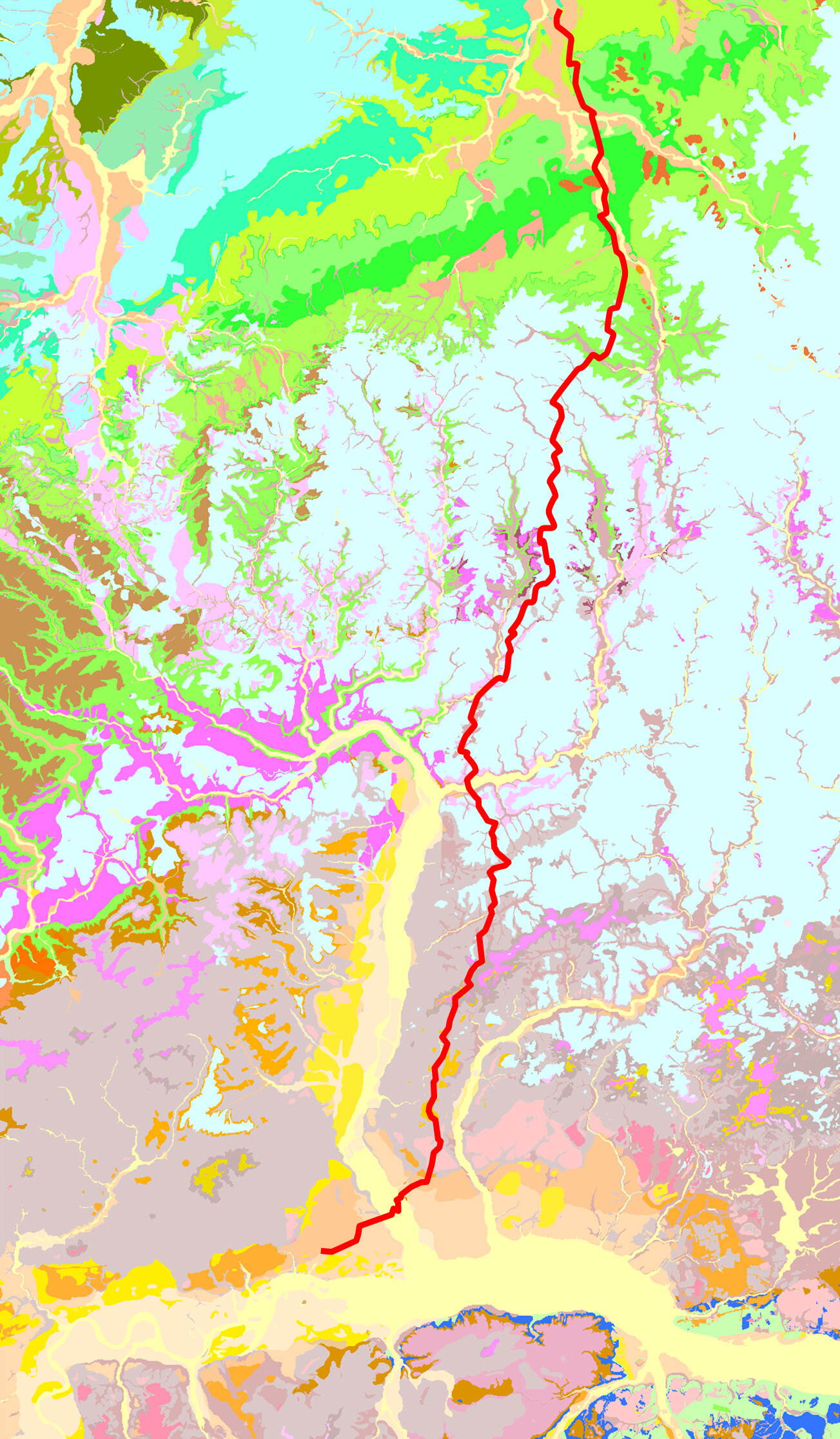

We start on the clay coloured pink on the modern geological maps and climb up the mud onto the chalk shown as green. The pink clay was formed last and filled the buckled bowl of chalk. At about half way to Cambridge we cross the extinction line. South of this the clays have London have felt the dainty touch of birds and mammals treading their surface, but never the massive dinosaurs that roamed the land when the chalk we tread today was forming at the bottom of nearby seas. The animals that made the chalk like the birds and mammals that survived the castrophe of the mexican asteroid that wiped their dinosaur cousins off the world, are still busy making more chalk in the plankton blooms today.

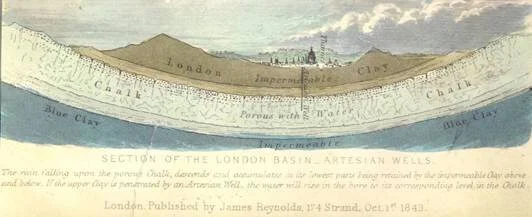

Not long after geology was discovered as a science two centuries ago it was realised that London was sitting on a chalk bowl full of clay. Our victorian ancestors dug wells into the chalk and fresh clean water gushed up from the great chalk sponge where the rain on the hills around London ended up trapped by more clay below. The same thick chalk that is broken clean into the sea cliffs by the English Channel at Dover.

The London clay was great for building tube tunnels and keeping fresh water separate from the filth of the river. Great for bricks but not so good for skyscrapers until twentieth century concrete and steel piles could be rammed into it, carefully avoiding the underground tunnels.

My modern cross-section below uses the old fashioned victorian colours and shows how the top layers of harder chalk have withstood the hammering of wind, rain and ice better than the softer layers below. Our route takes us across 100 million years of life’s debris from modern mud with modern fossils just a few tens of million years old or less in London to the ancient mud of Cambridge one hundred million years older. We are going back a miillion years for each kilometre we walk!

As we cross onto the chalk at Upwick Green we are crossing an extinction event that happened about two thirds of the way back at 66 million years. This was probably the last of the big ones, at least until now, and around 75% of life species disappeared in just a few years including all the dinosaurs that roamed the world when the chalk was still settling in the warm seas that once covered the earth we are treading today. This event was almost certainly caused by the asteroid that hit the gulf of Mexico five thousand miles from where we are walking today.

Eight hundred thousand years ago, nearer the warmer start of our current Ice Age the waves of ice advancing south, had not yet frozen and pushed the river down to London where it is today. The ice was advancing slowly and the north sea was lower and our ancestors could still wander all the way from Africa on dry land. There was no English Channel or white cliffs of Dover barring this land from later visitors and inclining it towards its sea faring future.

As the winter ice continued to thicken faster than the summer thaw, piled up to a mile or more thick as it edged slowly south. This massive weight pushed the whole of the north of england down further into the molten rock below, but a wave of climate warming around 400,000 years ago meant the ice stopped and the south of england was spared the weight of ice, leaving it pushed up like a see-saw as the ice sheets melted to flow where the Thames runs today and flood the north sea and breaking the landbridge at the white cliffs of Dover.

Today the ice is still receding and the London end of the see-saw and the whole south of england is now settling down as scotland and the north are still rising slowly back upwards relieved of their fat white burden.

At a place called Happisburgh on the East Anglian coast the ground is still sinking slowly lower and being bashed by the melting ice topping up the north sea and new cliffs are forming as the weak young earth crashes down to the beach.

The well trodden earth

A present from the distant past

We are not the first people to set foot on the ground by the banks of the muddy Thames

… not by a long way

In May 2013 just 8 years ago some human footprints on a beach at Happisburgh in Norfolk, England, were discovered and carefully photographed by scientists before being destroyed by the tide shortly afterwards. Careful research identified the prints in the dark mudrock above to be 800,000 years older than the modern boot prints in the sand next to them. The low cliff in the background preserves the layers of the 800,000 years of debris that had piled up slowly ever since, until the beachcombing scientists monitoring the layers conviently exposed by the restless sea, stumbled upon this; present knowledge read from another page turned over by the tide at our feet.

This same layer revealed something about what else we were up to as we wandered around in this part of our world, between the waves of ice, eight thousand human memories back. This simple lump of stone washed out from the same unassuming cliff was skillfully fashioned by someone with a brain a lot smaller than ours and feet a bit smaller too.

The flint rock that they used would itself have been washed out of chalk layers 60 times older and deeper below the banks of the river they trod. Further south up river but pushed upwards and exposed not far away to the south, the same broken chalk layer we will be treading on our walk that we mined for this diamond hard sharp rock in East Anglia for hundreds of thousands of years. Until we had the brains and time to discover and extract metal we lived off sticks and stones that we found or dug from the ground. The hardest and sharpest were best for cutting and killing and in their long times, much more precious than any gold or diamonds are today.

By Portable Antiquities Scheme - http://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/512140, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20375347