Walking all day

For most of our history and all of our prehistory, walking or running would have been a big part of all of our lives. Our feet were made for walking and our souls for roaming free.

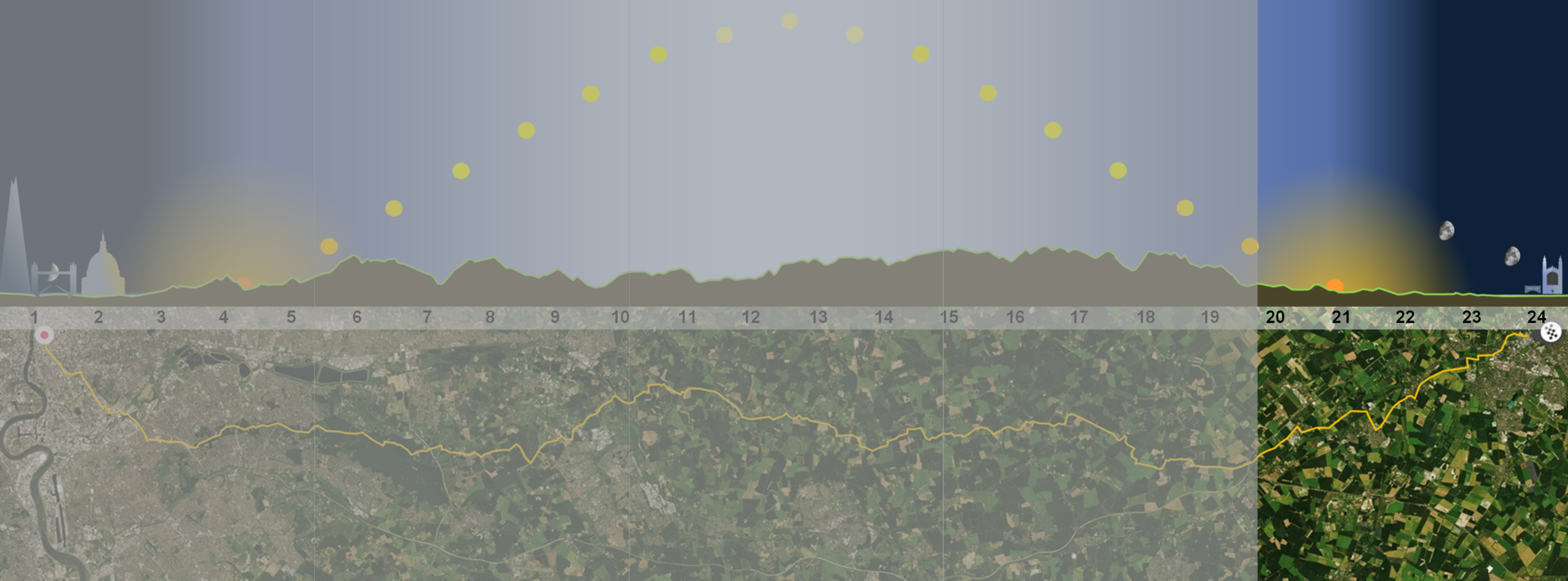

Today, all day, we’ll be on our roaming feet heading as far north as we can from well before dawn until dusk or bust.

The conquering Romans paced their marching routes in miles. A thousand (mille) paces gave the mile its name. Each roman pace was set at five roman feet from the point a heel leaves the ground to where it lands again. Legs and feet grew longer and today’s standard “land” mile grew too.

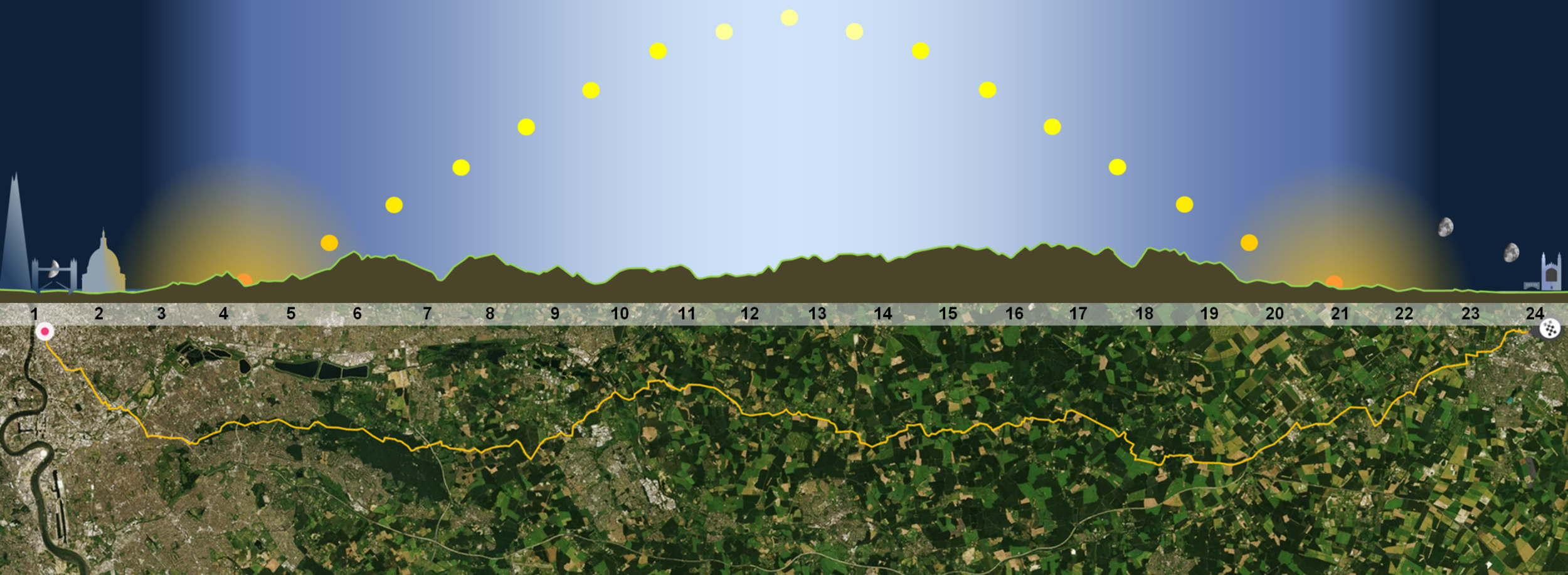

Our planned route to Cambridge, today takes us one hundred kilometres, that’s over 60 statute miles to cover by midnight.

Counting steps was not much use at sea, (unless the sea was frozen as more used to be), but degrees of latitude were easy to measure by checking the height of the sun at noon or the “pole” star at night. On the open ocean, if you kept your bearings and stayed on your latitude, you were sure to keep going in the same direction and eventually reach land. If you lost your sextant and your bearings you risked circling around until you ran out of water or hit some rocks hidden below the waves. Sailors stretched their sea legs and made “nautical” miles, conveniently equivalent to one sixtieth of a degree of latitude. On our green and pleasant land today, sixty “nautical” miles north would take us one whole degree of “latitude” further up away from the sun towards the north pole.

The pole star gave sailors latitude but it took time, and an accurate seafaring clock, to measure it, and give them longitude. We will be walking north along the meridian that got its name from the work of scientists up on the hill at Greeenwich desperately searching for more accurate ways to make life safer on the high seas.

Even if we stand still all day, we will travel 360 degrees as we spin around on the earth from midnight to midnight. At our latitude this is around 15,000 miles a whole lot further than a polar reasearcher spinning slowly on his spot at the ice at the pole but not quite as far as someone at the equator.

We estimate that even before we start to walk we will already be racing eastwards out of the shadow of the night at 637mph on our spinning ball. Around midnight when we head off briskly through the “auld” east gate of Londonium up the Mile End Road, we should be pushing our peak speed to 640 heading straight for the heart of the sun, before we spin down away from her and turn up north towards the pole.

The lines of latitude are shorter as we climb the globe so we spin slightly slower every minute north, losing 80 mph if we gained a full degree this day.

As we near Cambridge we will veer slightly west, vainly trying to keep up with the sun and turn the dial back to an earlier time. At four minutes to midnight we will have completed our spin, but over the day the whole earth has moved a degree further along its orbit around the sun (or the sun around the earth as folks used to think) adding an extra four minutes of time for us to catch it.

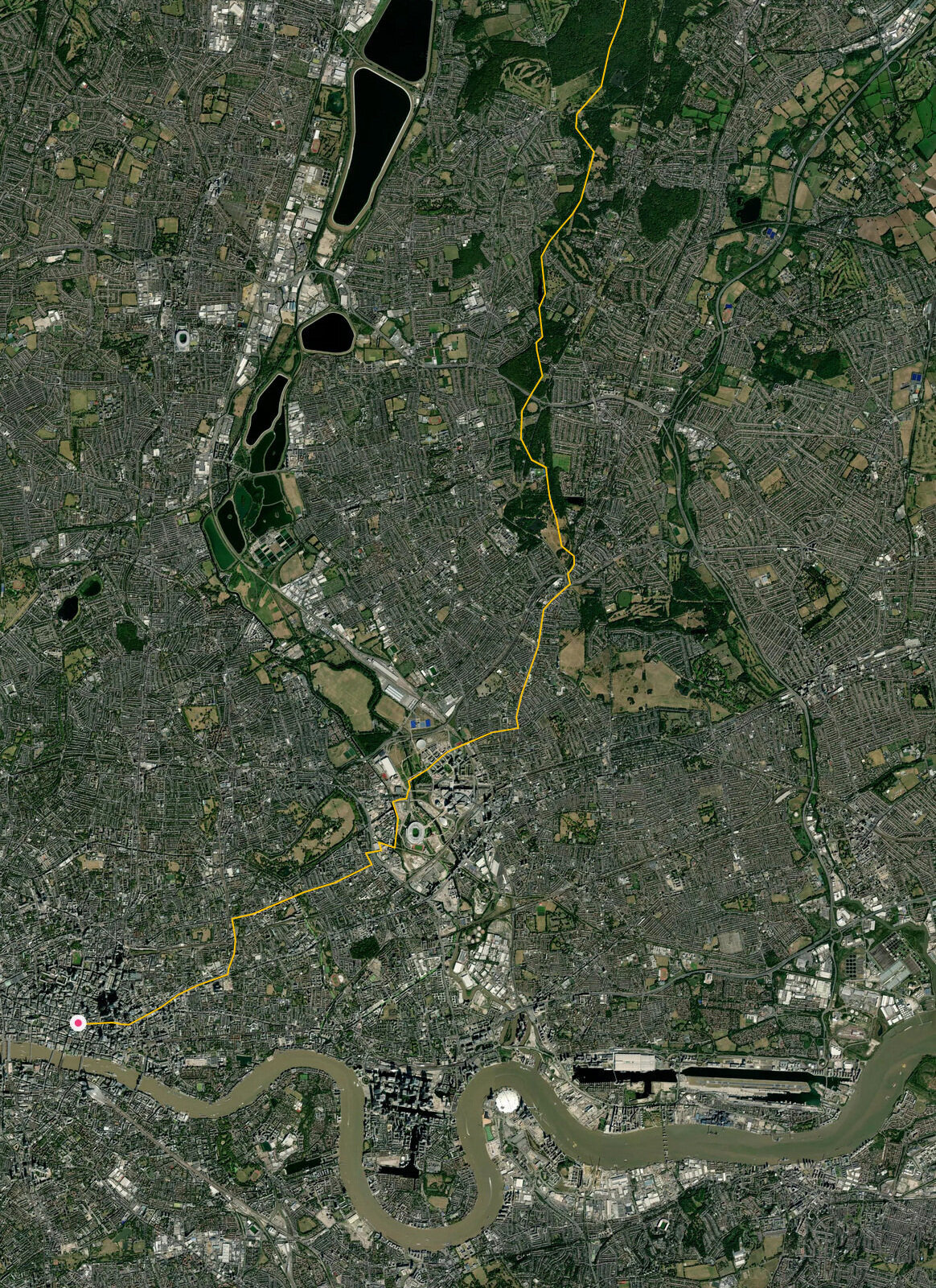

Our route takes us east along the river out of the glare of the London, until we cross the River Lea and turn north to climb through the suburbs, before wending our way through a remnant of ancient forest as dawn breaks to day, then across the M25 bracelet into open green fields bathed in the midsummer sun until darkness falls on us in Cambridge .

Leg by leg

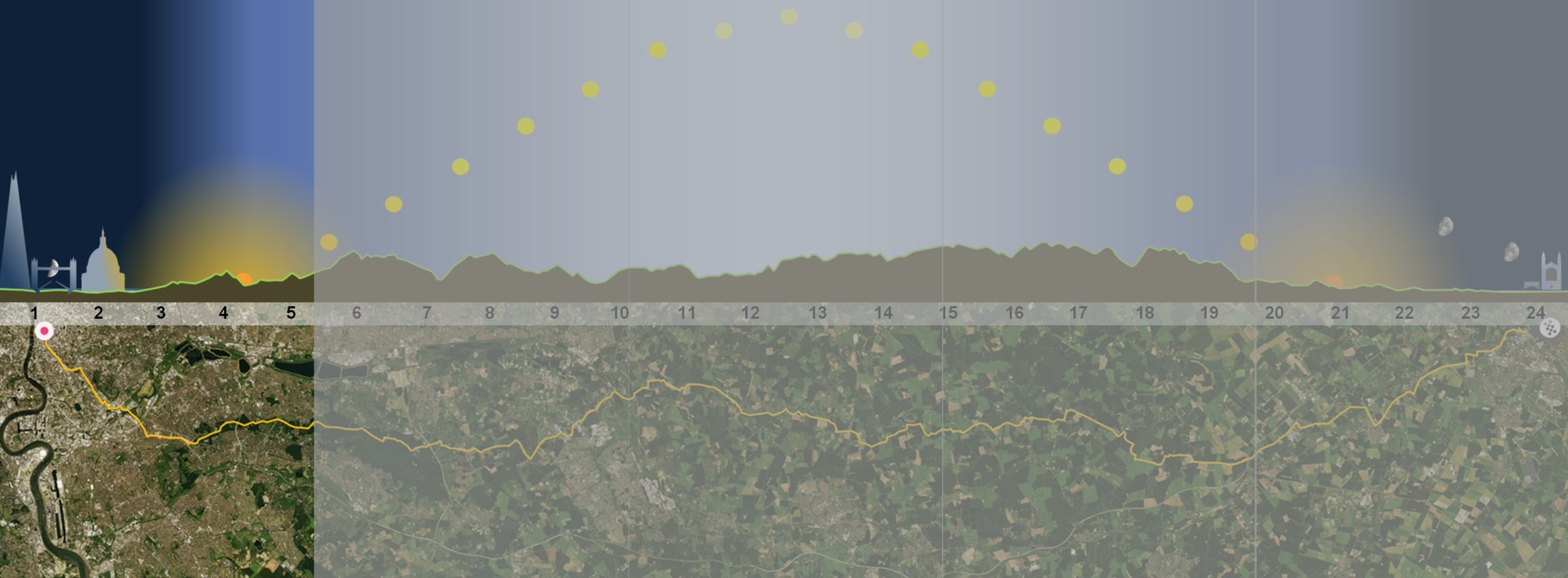

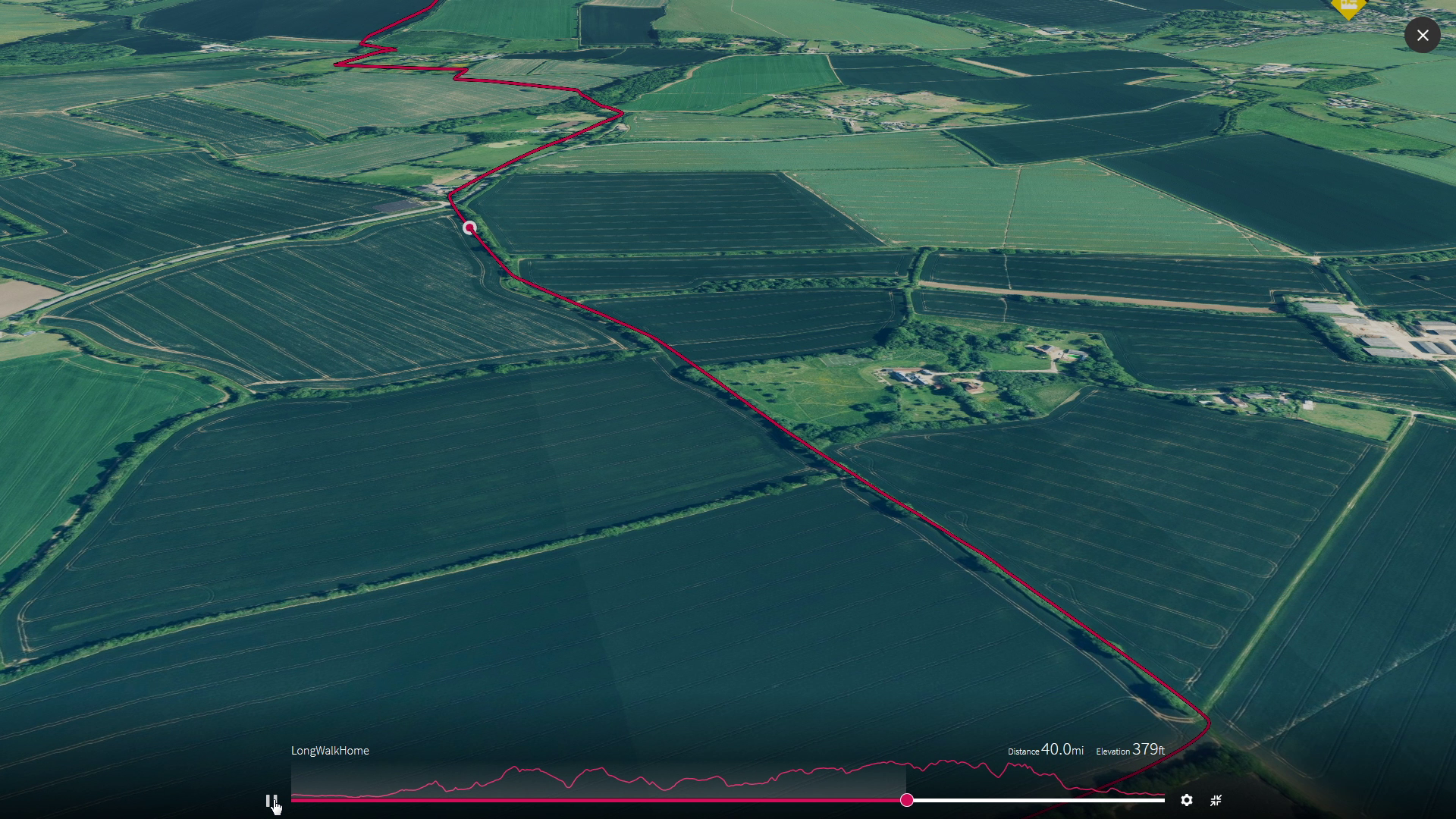

We have broken the route into five legs of about 12 miles. Each should take us about four hours and, with breaks, get us to Cambridge in twenty four hours. Select one to jump ahead or scroll the page to amble down.

Our first six thousand paces take us east, just up from the mighty loop in the Thames at Greenwich, to cross over the River Lea and the famous meridian at the bright oval of the olympic velodrome before veering north up through Leytonstone and up the muddy finger of green that still reaches right down into London.

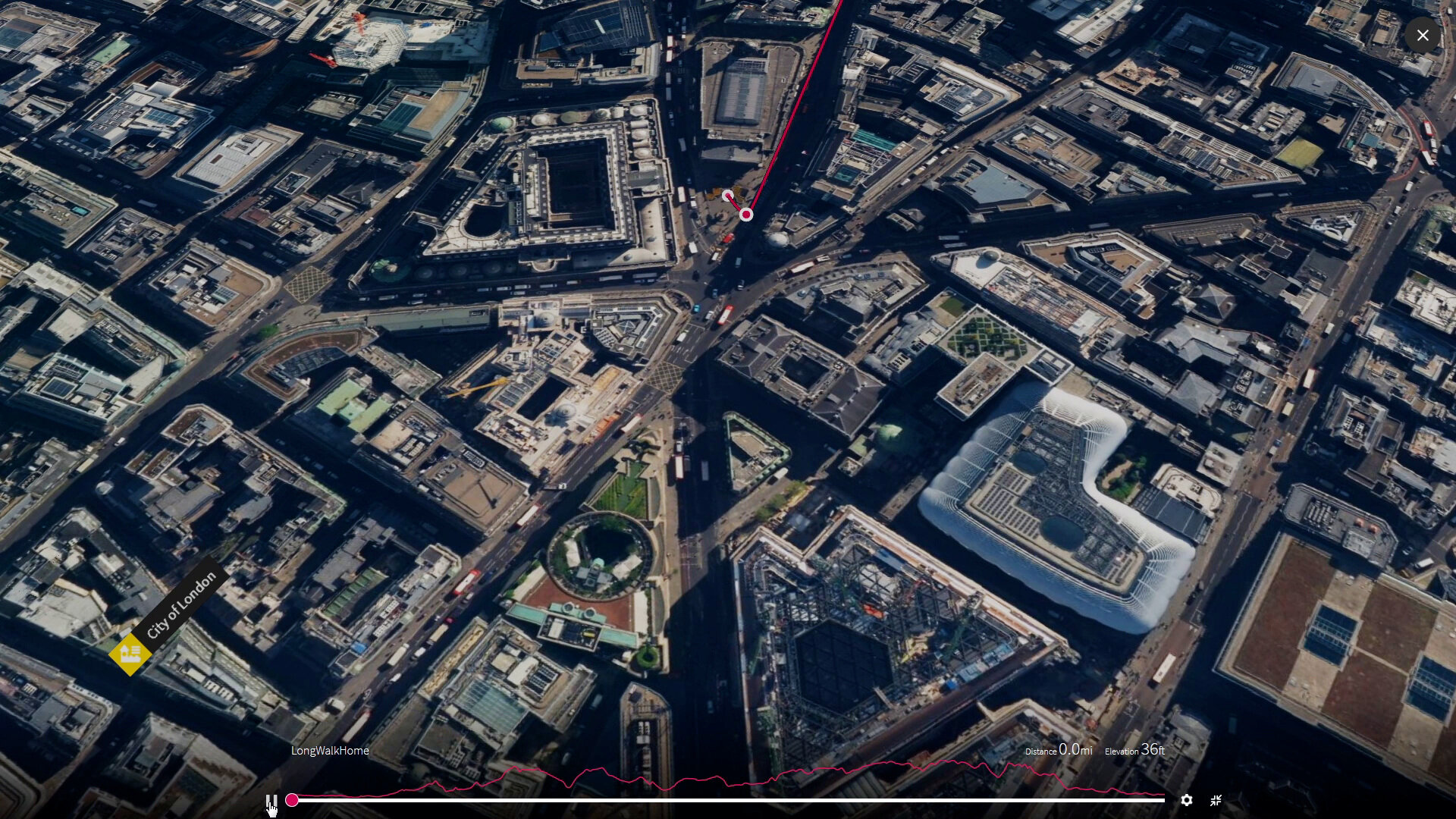

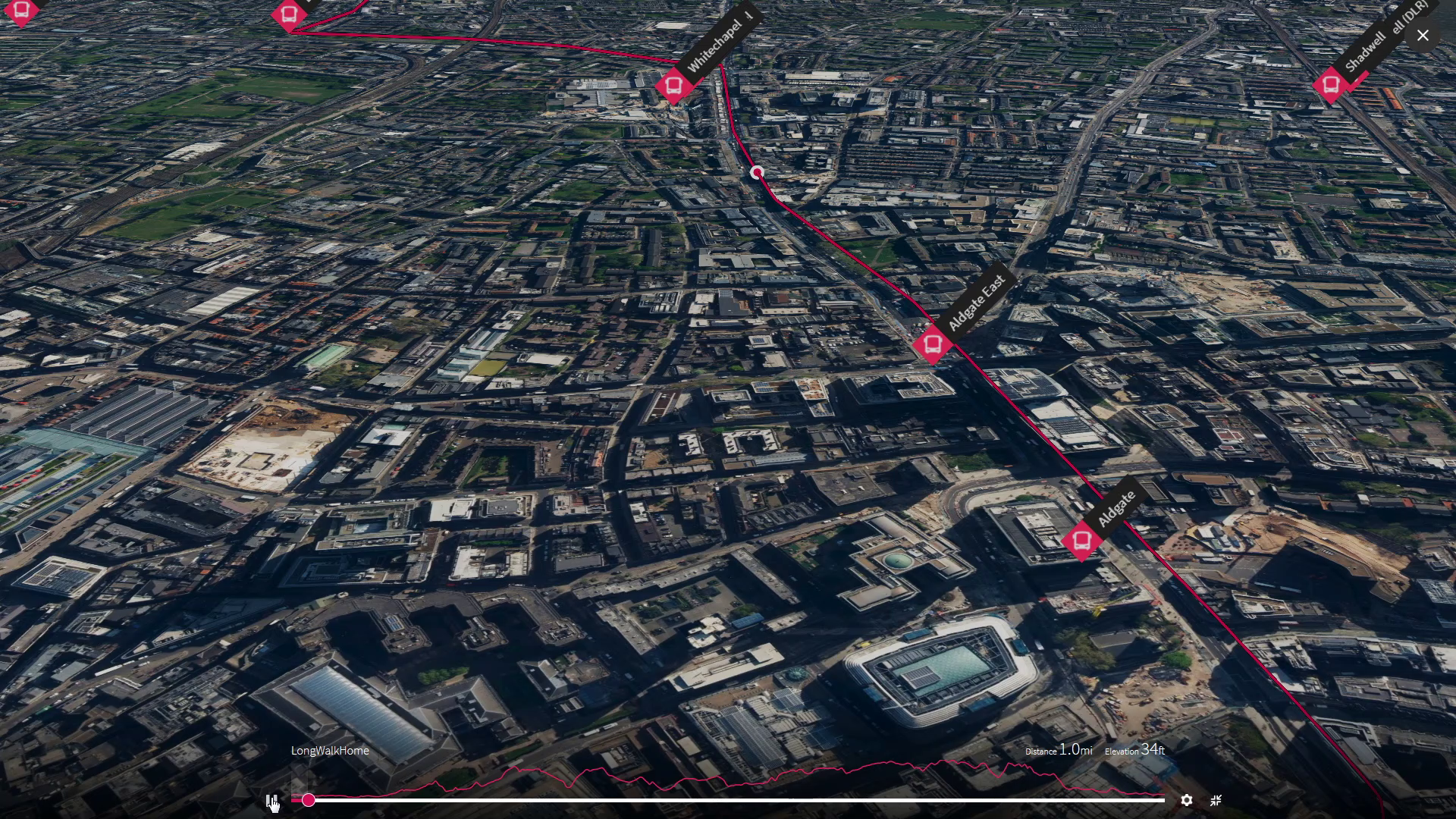

Milestones - Leg 1

Soar over us mile by mile as we head out of town on this first leg by seelcting each image

starting line

MS 0 is the centre of London just 2000 years young where eight streets meet at Bank. My daily commute used to end at one of the buildings down there. After walking just half way to our first milestone off the top of this view and we will already be out of the city that contained the whole of London for 1300 years, after Londinium was deserted by the Romans. It was only in later medieval times that monasteries started to spread beyond the walls, caring for the sick at St Barts, Charterhouse and St Thomas’s south of the river. By the Bishop’s Gate on the road north to Ely, the priory and hospital of St Mary Bethlehem jostled fore pole position next to the white Hart Inn. Beyond it were fields before another Augustinian Infirmary and abbey that retained its liberty and land at the edge London to become Spital’fields and for a few years another end for my London commute.

… more Within the city walls

To the mile end

For around 1500 years the trading town of London on the north bank of the River Thames was confined within its one square mile by the walls its roman founders built. We will start in the middle and walking for ten minutes eastwards will be over the wall and out of that City. Passing through Aldgate (the “Auld” east gate) we will walk the first mile out of town and turn north at the mile end and up Cambridge Road, just opposite the London Hospital.

On the road to cambridge

Just up the Cambridge Road we turn east again to join the Roman Road through the east end to Strat - ford where the romans crossed the River Lea in 43AD as they came, saw and conquered the Ancient Britons as they had the Gauls razing the stonghold of the “Camulo” and building the first roman colony , now Colchester, on top. It was the first and most important colonial town in Britain until Londinium overtook it. Both were burnt down by an angry british woman less than twenty years after they were started when the romans upset her by wantonly violating her family and then when they mistakenly left them unguarded whilst attempting to conquer the druid tribes in the hills of Wales, she wreaked her famous revenge.

Over the Strat Ford on the river lea

Nearly two thousand years later the whole world was invited to London to watch the 2012 Olympics in the stadium built by this ford on the River Lea before it flows south to join the tidal Thames, at the the famous loop of the river at Greenwich. It was here over three centuries years ago, after the over hasty revolution that killed his father and started the bloody english civil war, that the newly restored King Charles II sponsored the Observatory on the hill overlooking his royal palace at that was then outside London.

Science, shipping and inter-continental trading were starting to flourish and scientific instruments like telescopes and microscopes were allowing the curious to see way beyond what they had seen in the past. The king was keen to embrace the new, distance himself from the divine right of kings and keep his head, especially if it promised to make money and restore the nation’s economy. It was up there on that green hill across the river and over time that the astronomers he appointed got their naval heads, around our spinning ball and made clocks that kept their time and place when far out at sea so guiding sailors safely up, down and around the whole world until, their successors came up with GPS..

up the spur Spared by the weather

After crossing the various Greenwich Meridians that those royal scientists dreamt up, before they agreed on one that stood the test of time, we turn north up the narrow ridge of mud left between the Lea and the next river that cuts down through the mud on the other side and washes it out on the tide with all the ships that have sailed to ply the shallow north sea or venturing across the deep oceans encircling the world.

As we venture upwards we can look righteously down into the shadowy valley to our west at the swerving rails of our commute by the meandering Lea. The pits robbed of gravel to build London now reclaimed by water, that so often reflected the morning or evening sun through train windows on weary faces, but today we breathe the fresh forest air and feel the morning sun between the trees.

As we climb the ridge left between the rivers, we cross the furthest point south that the ice ever reached on this jumbled lump of earth now called “Britain” still pushed together by continental drift over millions of years from the distant parts of the world where its rocks once grew. Somewhere around here where we walk today, maybe 400,000 years ago high cliffs of ice marked the edge of a vast permanent sheet of ice maybe kilometres thick freezing and blocking all the rivers it crossed as it edged futher south for tens of thousands of winters, until the weather warmed and the ice melted more in summer and the water released round new routes to the sea. The Thames found a new way down from the hills in the west and the water in the Lea valley beside us, that used to flow north in the direction we are walking to reach it, now flows south to help it push London’s ships straight out to sea. The sea level rose and Britain became an island again.

Savouring the forest

As the ice melted, rocky debris was left behind, strewn over the clay up here atop the ridge and not yet washed away. This was not so great for farming so the wild trees were left alone. Until London finally engulfed this ridge, this Ancient Forest survived almost intact, but it was the action of a few that ensured this remnant still survives for us to enjoy today as a leafy route out from inner city London and beyond the girdle of the M25 today. As we climb through Leytonstone to enter it, we pass the house of the man called Buxton who helped local people save this forest and Hatfield Forest beyond and founded one of the worlds first conservation charities that we are supporting today.

We hope to enjoy the dawn song of birds in the forest, as we enter the next leg to cross the cordon of the M25 and escape the urban sprawl of this global city London has become today

Crossing the motorway girdling London and into open farmland before dropping back down to cross the River Lea again and the familiar railway at Roydon.

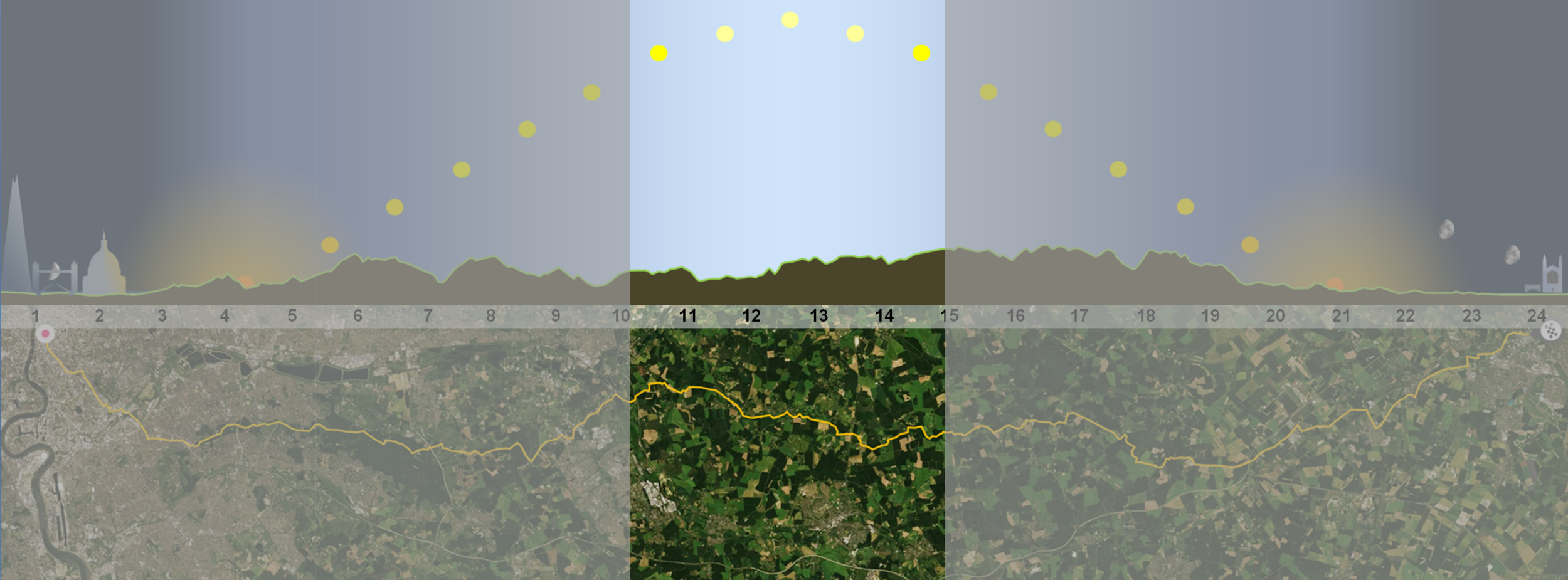

Milestones - Leg 2

Soar over us mile by mile as we head onwards, by selecting each image

High Beach

After our climb up through the forest to High Beach we are back down the cool valley for a breakfast stop as we cross the River where it splits into three. The Lea carries on to the north west and its source in Luton and we will cross the Stort as it heads east, so that we can carry on up the Ash the smallest branch heading north and taking us back up onto the ridge and out of this gap that was cut by the Stort.

Over the M25

On a May Satruday afternoon in 2021 during Covid

Sometimes this leg of the journey takes us up across the flat open fields strewn with debris from the ice and sometimes we wander along side the River Ash at the bottom of the valley that it has washed right through the London clay. We will hear the cool water bubbling over the chalk and see it stirring the gravel or glimpse a brown trout.

Up out of London’s mud bowl and onto its chalk white rim

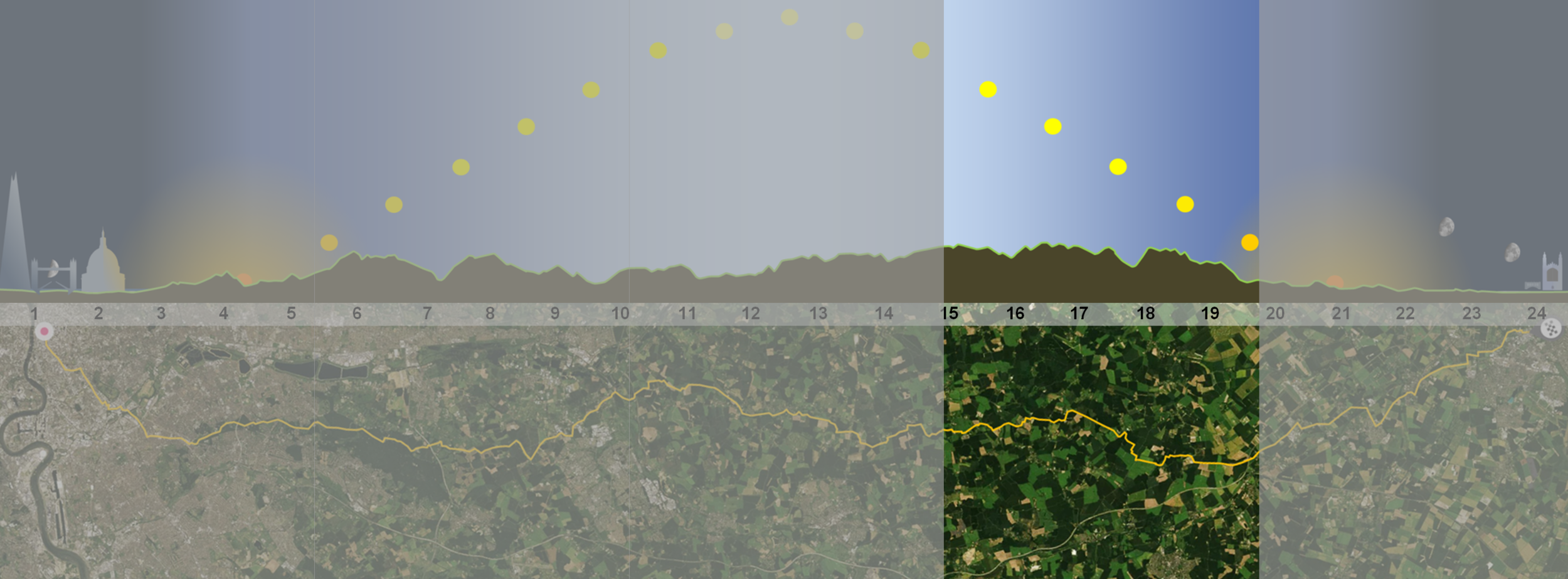

Milestones - Leg 3

Soar over us mile by mile as we head onwards, by selecting each image

This leg of our journey takes us across the broken soft strata of the generations of tiny sea shells that lived right here capturing carbon and calcium for millions of years sinking to the bottom of their warm sea before the climate changed and extinguished them to be buried under the mud of some newer lives in very different seas. Where we start this leg the rivers flow back down south to London but by the time we finish we have joined the springs and brooks that flow north, with us, and on past Cambridge to the sea.

We are walking over the broken edge of the thick dish of chalk that now contains the clay of London. Over millions of years whilst the dinosaurs roamed the land, the microscopic sea life that was here dropped dead day be day like the algae blooms still are in the seas around us today. The chalk was up to 200 metres thick here by the time the asteroid struck and the dinosaurs went making way for us mammals and the sea level dropped and clay started washing down from nearby land and dropping on the sea bed instead, before the whole of southern england was gradually buckled as the drifting continent of Africa pushed up and made the alps

Milestones - Leg 4

Soar over us mile by mile as we head onwards, by selecting each image

This leg takes us over the harder edge of the oldest chalk and steeply down onto some softer ancient mud as we arrive in Cambridge where we finish our journey, but the water and life flows on, under the bridges filtering through the flat wetlands around the Isle of Ely, once are larger town than Cambridge nourished by the ducks and eels that lived around it and where passed lives dropped to the dark depths of its marshy black fens trapped as carbon maybe on its way to become coal.

Now we drop over the sharp end of the old hard chalk brim and drop steeply down to reach the even more ancient mud underneath it before we arrive at Cambridge on the edge of the newborn earth settling amongst the reedbeds of the few young flat, undisturbed and still living fens

Milestones - Leg 5

Soar over us mile by mile as we head onwards, by selecting each image